ARCHIVES 2012

International Fantastic Competition

Short Films Competition

Opening / Closing

International Fantastic Competition

Crossovers Competition

Midnight Movies

Documentaries

Special Screenings

International Competition

Made in France Competition

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

SPLENDOR IN THE PAST

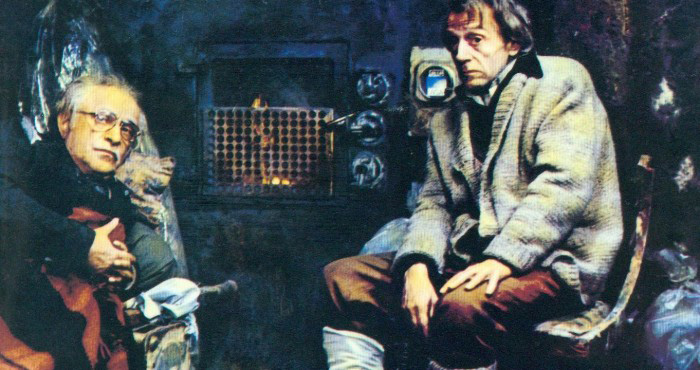

Michael Powell (1905-1990) and Emeric Pressburger (1902-1988) formed one of the most creative partnerships in cinema’s history. They worked under the banner of The Archers, founded to develop their filmmaking art without interference. Their best films were shot between 1940-1951, including, besides those in our selection, classics such as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and A Canterbury Tale (1944). If Powell was in the director’s chair and Emeric generally provided stories and dialogue, their famous but little understood credit line: “Produced, written and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger”, testified to the intimate ties that bound every aspect of their work. Their collaboration was rooted in a fertile cross-culturing of talent between men of different backgrounds and temperaments: a discreet Hungarian Jew who fled Hitler’s Berlin and the extroverted Powell, gentleman from Kent, quintessentially English. They were maverick artists, far removed from the British realism of the times. They made films of visual magic – fantasy-filled, flamboyant, excessive – but which never overshadowed human emotion in very real stories about love, death, sacrifice and artistic creation.

But like the rainbow in the sky, The Archers could not last. For Powell, they lost their “glorious arrogance in 1953”, but their partnership was not officially dissolved until 1957, in disagreement over their independence in the new face of British production. The films, with their creators, fell into obscurity and were almost for- gotten until a series of revivals began in the 1970s. Their reputation spread to America in the 1980s, when an overwhelmingly enthusiastic Martin Scorsese brought Peeping Tom to the New York Film Festival, where it met with great critical success. Powell eventually became his advisor in America and they remained friends for life. Powell and Pressburger, filmmakers who inspired giants – Scorsese, Romero, de Palma, Coppola, Spielberg and others – rekindled and deepened their friendship until Emeric’s death in 1988.

Post Apocalypse

APOCALYPSE YESTERDAY

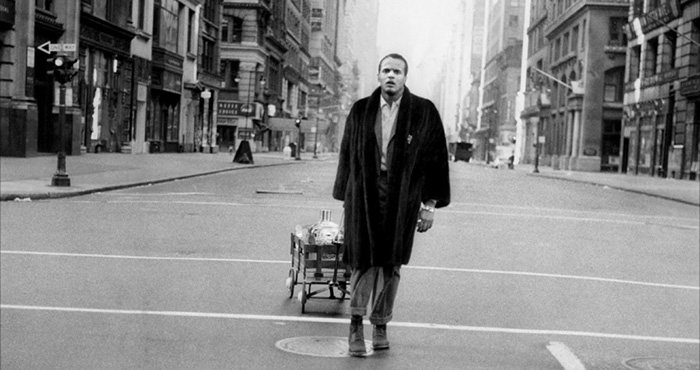

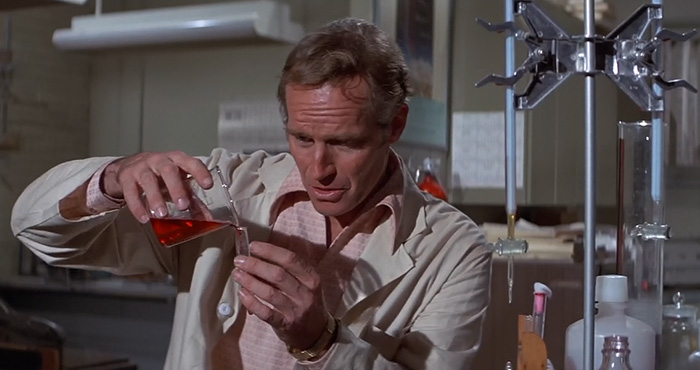

Among cinema’s vast array of themes, one which has hardly been dealt with is the kind of world we would be left with in the aftermath of an apocalypse, a term generally used to imply human extinction due to all-out nuclear war. The meaning of extinction, however, is a relative one in that the writers of our 10 revival films, cinematic conventions oblige, have left us with a few survivors roaming about in nightmarish landscapes, and who have returned to humanity’s initial state of survival-of-the-fittest, consequently more savagely aggressive than ever.

If we take a look at the stars in these films, putting aside Harry Belafonte, Mel Gibson, Kurt Russell and Michel Serrault, our eye falls upon Charlton Heston and Yul Brynner. These two actors played diehard enemies in Cecil B. de Mille’s The 10 Commandants in 1956 before moving on to specialise in the Eternal with edifying Biblical roles: Heston’s Ben Hur in 1959 and Brynner’s Salomon and Sheba in the same year. Then they both recycled themselves admirably over the next two decades, playing in a few pessimistic sci-fi films, notably for Heston, The Planet of the Apes in 1968 followed by Soylant Green in 1973, and for Brynner, Westworld in 1973 and The Ultimate Warrior in 1976.

The Post-Apocalyptic revival films may well belong to the past, but their implicit warnings still ring true today. To resume: it’s time to stop playing the sorcerer’s apprentice as we have been doing over the last fifty years. Ecological meltdowns, energy shortages and pandemic death threats – all have shiny, new apocalyptic potential, making Dad’s list from yesterday a quite extendable one.

Jean Alessandrini