ARCHIVES 2010

Opening / Closing

European Features Films Competition

Special screenings

3D session

European Competition

Made in France Competition

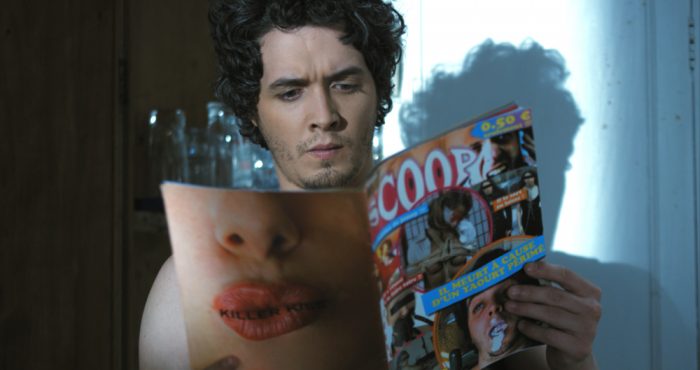

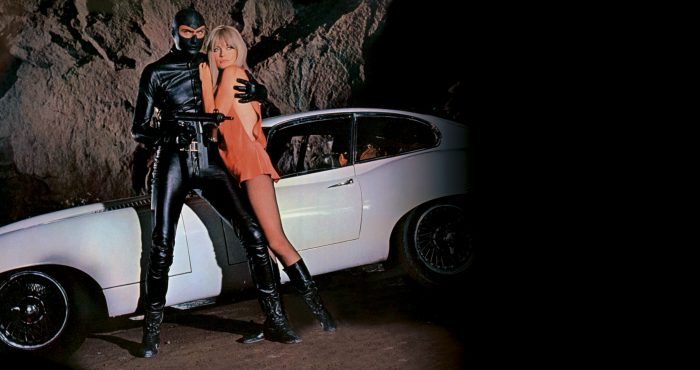

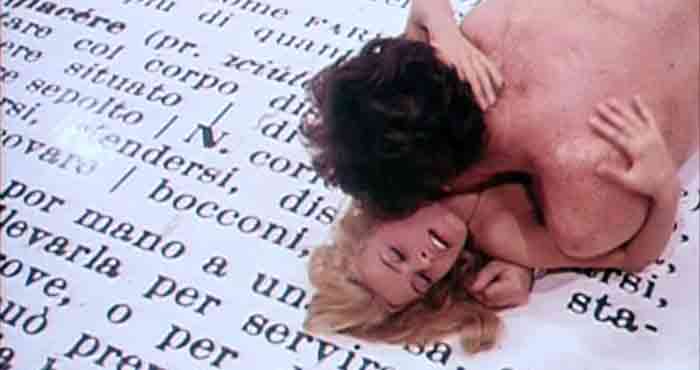

Italian Pop

In the late 1960s, the Italy of the sexual revolution, of student protest, of the musical comedy Urlatori alla Sbarra (Screamers in the Bar), the Italy that dreamed of Swinging London, progressive rock and the Valentina comics. This Italy finally discovered cinema. It could not have happened otherwise, because at that time everybody was looking to the cinema for something new, something that would mirror the times and invent the future. A movement was born, with ill-defined contours, which for convenience’s sake we call Pop, but which was in fact a tumultuous expression of different social needs.

It is no coincidence that all sorts of people had a go at it and at different levels: both high-brow and popular. Each with its own ideals and objectives, but all oral most all committed to reinventing the genre. One could say that Blow Up (1966) by Michelangelo Antonioni, is structurally a giallo, as Elio Petri’s La decima vittima (The 10th victim, 1965) is a science-fiction movie, without detracting from the intent of the “authors”. And while Roberto Faenza and Bernardo Bertolucci loudly claimed auteur status in such films as Escalation(1968)orPartner (1968), others such as Piero Schivazzappa (Femina Ridens 1969) (The frightened woman) and Alberto Cavallone, who wrote the dialogue for the Italian version of Radley Metzger’s The Lickerish Quartet (1970),didn’t give a damn about the image, music and bodies of their characters.It was a new type of cinema which had nothing to do with Italian neorealism, and was made up of heightened colours, sounds, geometric shapes, and bold shots. These elements became the heritage of that whole period of Italian cinema, which still retains some of its traces today.

One has only to think of the directorial choices made by Sergio Martino in films of a totally different depth such as Tutti i colori del buio(All the Colours of the Dark) (1972), which is none other than a sort of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) with a Pop dressing. To a great extent much of it is also due to the music and to so many musicians such as Bacalov, Umiliani, Morricone, Cipriani, Rota, who invented a genre without even knowing it or imagining that years later it would be described as “lounge music”. And then there was the desire play around with cinema and contaminate it with other media, such as comic books for example. The modern comics of such authors as Crepax and Bunker. Mario Bava directed Diabolik (1968), Piero Vivarelli, Satanik (1968), Umberto Lenzi, Kriminal (1966) and Corrado Farina, Baba Yaga (1973), endowing the heroes and heroines of the comic strips a three-dimensional existence, while Tinto Brass, in Col cuore in gola(DeadlySweet1967),went so far as to construct a comic book on the big screen. All looking for a modern audience that no longer existed.

Val Lewton

In 1942, RKO-Radio Pictures was almost bankrupt after producing two expensive films for boy genius Orson Wells, which, in spite of critical acclaim, were major box office flops. The studio set up a B-horror film unit, hoping to recuperate its losses by turning out films to compete with Universal’s monster films. Val Lewton (1904-51), Russian-born writer, story editor and right-hand man to David Selznick, was hired to produce the films and head the unit. He had to make low-budget films not exceeding 75 minutes and to fit them to a predetermined title. Lewton assembled a team that included Jacques Tourneur, editors Mark Robson and Robert Wise, and writer DeWitt Bodeen. (He would later give Robson and Wise their first shot at directing.) RKO did not get what they were expecting from Lewton, who rejec- ted most B-horror film conventions as cardboard cinema, but they got much more. Lewton gave them psychologically complex films of rare visual poetry, where the familiar – subways, streets,swimming pools – became places of dread and anxiety. Evil was not found in eastern European castles, but in ordinary people who in some way life had turned upon. His characters were drawn towards death, at best they sought out the unorthodox and strange. Lewton produced 9 horror films for RKO. Though finely directed by Tourneur,Robson and Wise, they bear the unmistakable Lewton stamp and his pessi- mistic vision of the world. It was he who rewrotethe final screenplays, drew set designs and layered his films with sharp dialogue that was never the stuff of B-cinema.

RKO studio heads were disappointed when they saw Lewton’s first film, the monster-less and poetic CatPeople. But they misjudged. The film made nearly 4 million dollars and pulled RKO out of the hole.